The Unbreakable Habit: Why Governments Are Hooked on Debt

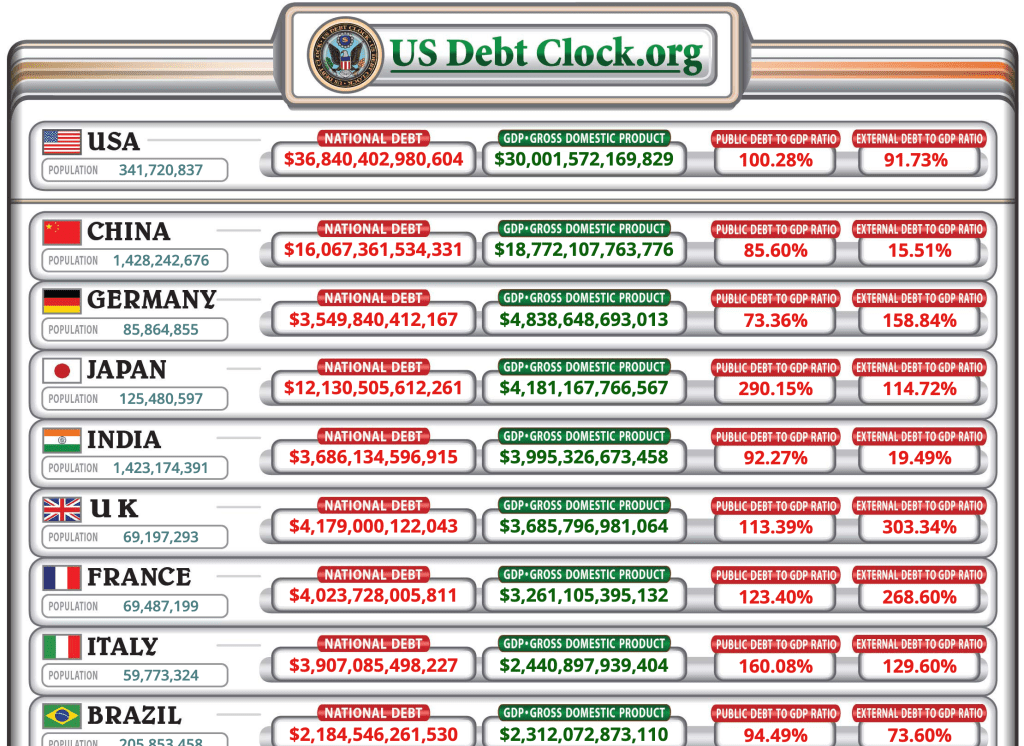

Imagine a world where governments operate like perfectly balanced households, spending only what they earn. A nice thought, isn’t it? But the reality painted by global finance is starkly different: governments across the globe seem to have developed an insatiable appetite for debt. From the towering skylines of New York to the bustling streets of Tokyo and even the historically frugal corners of Berlin, borrowing has become the norm, a seemingly indispensable tool in the governmental toolkit. This isn’t a temporary blip; many experts suggest it’s a deep-seated addiction with potentially serious consequences for the global financial landscape. Why this reliance on red ink? Let’s delve into the complex web of factors fueling this governmental borrowing binge.

The Siren Song of Spending Without Immediate Pain

One of the most potent drivers of government debt is the inherent political appeal of spending without the immediate unpopularity of raising taxes. Politicians often find it easier to finance ambitious projects, social programs, or even tax cuts by issuing bonds rather than directly increasing the burden on taxpayers. This allows them to deliver tangible benefits to their constituents in the present, while the responsibility of repayment is often deferred to future generations. It’s a tempting proposition, a way to seemingly achieve “nirvana” by increasing spending without immediate political fallout.

Furthermore, in times of crisis, such as the global financial meltdown, the COVID-19 pandemic, or geopolitical conflicts, governments understandably step in as the “insurers of last resort.” They deploy significant fiscal measures to cushion the economic blow, support businesses and individuals, and prevent a deeper collapse. This necessary intervention inevitably leads to a surge in government borrowing, highlighting debt as a crucial tool for navigating turbulent times.

Borrowing Our Way Out: A Recurring Playbook

The transcript highlights a recurring pattern: governments often “borrow their way out of trouble.” This approach, seen since the global financial crisis, involves using debt to stimulate economic recovery. The logic is that increased government spending can boost demand, create jobs, and ultimately lead to higher tax revenues that can eventually help service the debt.1 However, the risk lies in becoming trapped in a cycle where the primary means of paying for past borrowing is yet more borrowing, without a clear exit strategy.

The Comfort Blanket of Low Interest Rates (Until Now)

For a significant period, particularly after the 2008 financial crisis, governments benefited from historically low interest rates. This made borrowing relatively cheap and the burden of servicing existing debt manageable. In a world of near-zero or even negative interest rates, the incentive to take on more debt was strong. It felt like “free money,” encouraging a greater reliance on borrowing to finance various initiatives. However, the recent spike in inflation and the subsequent rise in interest rates have dramatically changed this landscape, making debt servicing significantly more expensive and exposing the vulnerabilities of high debt levels.

The Shifting Sands of Global Security and Demographics

Beyond economic management, several long-term trends are also contributing to the upward trajectory of government debt. An increasingly uncertain global security environment necessitates higher defense spending. Ageing populations in many developed countries put immense pressure on healthcare and pension systems, requiring substantial government outlays. The urgent need for a green transition to combat climate change also demands significant public investment in renewable energy and sustainable infrastructure. These are not temporary expenditures but rather long-term structural pressures that contribute to the persistent need for government borrowing.

The Specter of the “Bond Vigilantes”

The transcript introduces the concept of “bond vigilantes” – investors who, by selling government bonds, can drive up yields (interest rates) if they perceive a government’s fiscal policy as unsustainable.5 Historically, the fear of these vigilantes acted as a check on excessive government borrowing. However, the fact that debt levels have soared in many countries without a major market backlash has led some to question their effectiveness or even suggest that central banks are now the primary “vigilantes.” The point at which the bond market might “break” and force governments to confront their debt addiction remains a significant uncertainty, a ticking time bomb in the global financial system.

Not All Debt is Created Equal: A Matter of Perspective

Interestingly, the transcript also presents a counter-intuitive perspective. One economist argues that government deficits are simply the flip side of surpluses in the non-government sector, suggesting that this “red ink” is actually enabling “black ink” for the rest of the economy. Furthermore, the example of Japan, with its extraordinarily high debt-to-GDP ratio yet relative economic stagnation and low interest rates, highlights that the consequences of high debt can vary significantly depending on factors like domestic savings rates and the central bank’s actions.

The Path Ahead: Adjustment or Crisis?

The experts in the transcript paint a complex and somewhat worrying picture. While some argue for fiscal rules and spending cuts to bring deficits under control, others suggest that austerity measures could stifle growth.6 The possibility of “inflating away the debt” over time is also discussed, although this comes with the risk of unpopular price increases. The crucial question remains: can governments wean themselves off their debt addiction through gradual adjustments, or will it take a significant financial market shock to force a change in behavior?

Ultimately, the global reliance on government debt is a multifaceted issue with no easy answers. It reflects a complex interplay of political incentives, economic realities, and global challenges. As debt levels continue their upward climb, the world watches with bated breath, wondering when and how this unbreakable habit will be addressed.

What do you believe is the most sustainable way for governments to manage their growing debt burdens without triggering a major economic crisis?

Leave a comment